During Tuesday’s Game 4 between St. Louis and Chicago, a fracas in the Blackhawks end led a strange series of events.

Here’s a summary in less than 140 characters.

Given a questionable man advantage, Chicago capitalized, as Duncan Keith scored for a 2-1 lead.

When reviewing the play during the second period intermission, NBC analyst Keith Jones made an interesting observation. While I don’t have his comments word-for-word, here is roughly how Jones reacted to seeing the questionable call and the resulting Keith goal.

“So if you’re Chicago now, you have to play extra careful because the officials are going to be looking to give St. Louis a chance next.”

The insinuation from Jones is that with Keith scoring, the refs were going to be extra sure that the next penalty would be called on Chicago. Of course, that’s what happened next, as Andrew Ladd was whistled for interference a few minutes later. Vladimir Tarasenko scored for St. Louis, and the Blues eventually won 4-3.

Jones’ comments are right in my wheelhouse. It is well established that NHL referees (and perhaps those in other sports, too) are prone to make calls that even up each team’s total number of penalties. This can be termed a biased impartiality – in an effort to appear impartial, refs no longer make impartial decisions.

But if refs vary the frequency of even-up calls based on whether or not the team with the initial power play scored, it would add an extra dimension to understanding officials’ decision making.

So, I decided to look into whether Jones was onto something.

*****************

A complete analysis linking penalty likelihood to previous power play performance would take some advanced modeling techniques, given the difficulty in separating possible associations to other game factors, including score effects and the impact of overall penalty differential.

But if power play performance is impacting future referee decisions, an easy place to start would be to look at the game’s second penalty, while considering the following two questions:

(i) Is it an even-up call? (In other words, is it called on the team that did not receive the first penalty?)

(ii) Did the team on the first power play score?

By looking at penalties early in the game, there’s less of a chance that score-effects and complex penalty-differential effects are impacting referee decisions. Additionally, most NHL games have at least two penalties, so we are roughly getting one observation from each game.

It will also be easy to separate any possible effects by whether or not the home team was owed a penalty, as well as season type (regular, postseason).

*****************

As usual, I’ll use the nhlscrapr package in R. This includes play by play events from all regular and postseason contests since the 2002-03 season (roughly 27,000 games). I decided to drop penalties that were assessed simultaneously, as many of these are matching minors that did not yield a man advantage. However, results were similar when not doing this.

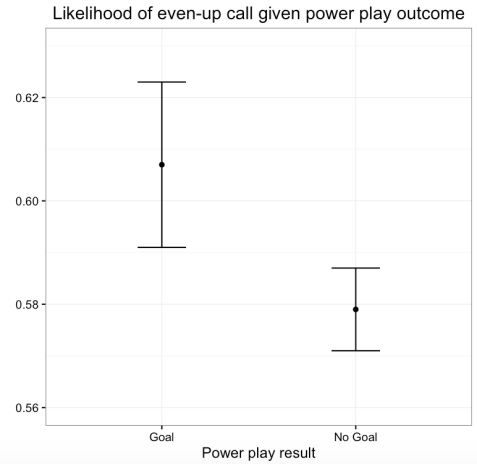

Overall, teams with the first power play of the game converted 19% of the time. When they scored, the ensuing power play was awarded to the opposite team 60.8% of the time. When they didn’t score, the ensuing power play was awarded to the opposite team 57.9% of the time. At a tick under 3%, the difference is statistically significant, albeit not an overwhelming one in terms of practical significance.

Interestingly, the results were much stronger in the postseason. Teams scoring on the game’s first power play were given the next penalty 69.3% of the time, compared to 62.2% of the time when they didn’t score, for a relative difference of 7.1%. Across all games, the difference of in make-up call likelihood was slightly stronger for the home team (3.2%) than the away team (2.6%), conditional on the first power-play chance being converted.

*****************

It’s far from exhaustive, but there does appear to be a possible link between power play success and the evening up of penalties, as initially suggested by Jones, the NBC studio host.

Of course, there are other factors at play, even in our simplified analysis. If teams score on the first power play of the game, they are more likely to be playing with the lead. And because teams with the lead tend to possess the puck less frequently, they are potentially more likely to pick up penalties. In this sense, looking early in the game, when penalties and possession are less likely linked to overwhelming score effects, is preferable. Interestingly, the effect of previous power play performance was actually stronger when the game was tied at the time the second penalty was called.

In any case, NHL refs wouldn’t be the first ones accused of basing calls on what should be independent factors. It’s not uncommon for NBA officials, for example, to be accused of a late whistle – that is, deciding whether or not to call a foul based on whether or not the offensive player’s shot went in. As in the NBA, where the refs may feel bad for the offensive player who missed a shot after a borderline foul, NHL refs could seemingly feel bad for the defensive team after giving up a power play goal after a borderline penalty.

Anyways, here’s a plot using the overall rates. As referenced earlier, not a huge difference, but not nothing, either.

*****************

*Here’s the code. It code took a bit of care, as the nhlscrapr package does not contain power play success outcomes in the set of play-by-play events. I considered a power play a success if there was a goal within 120 seconds of the penalty scored by the team that received the power play. Feel free to play around if you’d like – I’m using the grand.data file from nhlscrapr.

2 Comments